Norman Gilbert’s twin passions, for drawing and painting and for his wife and family, are celebrated in a new show in Fife this spring, with the 92-year-old artist showing no signs of slowing down

Photography Enzo Di Cosmo

Words Catherine Coyle

“Everyone has left,” explains Norman Gilbert. “That’s why there are no people in my paintings now.” The 92-year-old artist is preparing for a solo show, at Fife’s Tatha Gallery, where thirty of his paintings will be exhibited. He’s not being morbid, though.

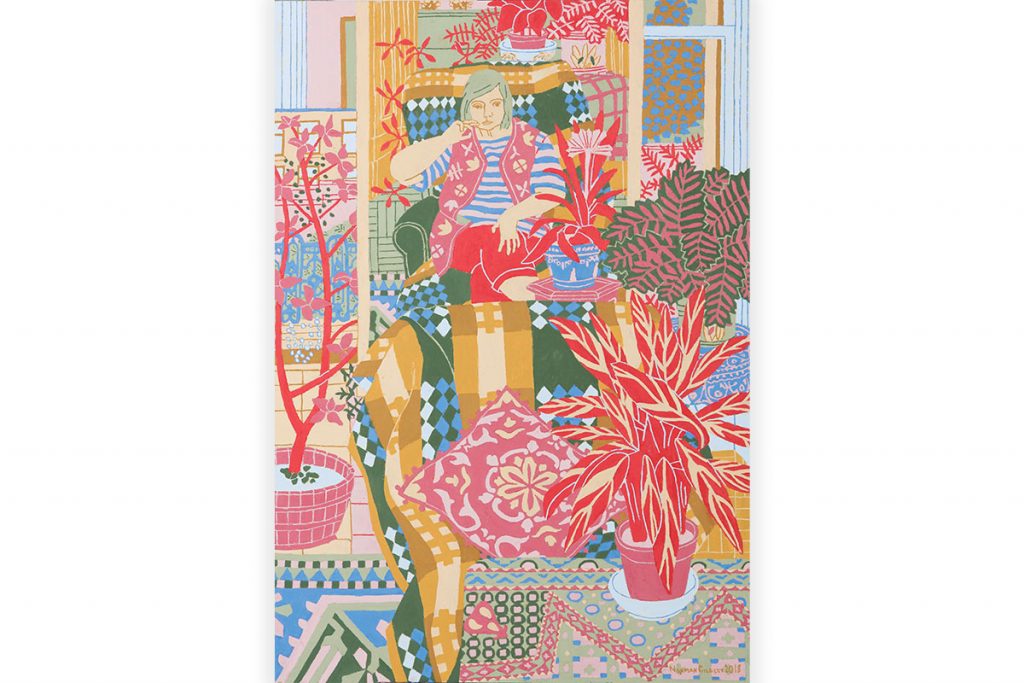

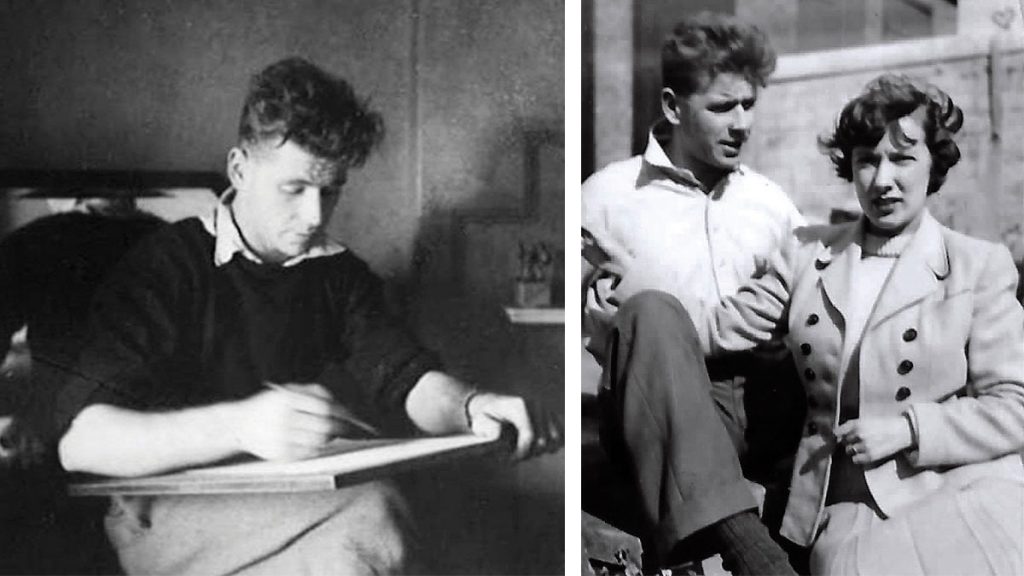

Over the course of his career, Gilbert has painted a lot of figurative work, always using the people around him as models. His vast back catalogue contains countless images of his four sons, Paul, Bruno, Daniel and Mark, and, latterly, their partners and children. But the central figure in Gilbert’s work, and the person he misses painting most, is his late wife, Pat.

“It’s like getting into a car by yourself and not knowing whether to turn left or right,” says the artist, who lost his wife in 2016, the day after their 65th wedding anniversary. Pat, who was already in the grip of Alzheimer’s, had also suffered a stroke. Her husband had been her primary carer, and, when she was admitted to hospital, he went with her.

“I started by drawing her hands,” he says, his eyes filling as he recounts how he coped during his wife’s time in hospital. “I wanted to make sure I could still do it. I forgot where I was, and I was just drawing Pat again.”

He recalls holding her hand and, although she could not speak, she squeezed his hand in return. The drawings he made during this period were displayed in a special one-off show last year. None was for sale (“I’ll never sell those drawings,” he says) and beforehand he was not convinced that a non-selling exhibition would work. “I didn’t think people would travel to see pictures they couldn’t buy, but I didn’t know I had such loyal, intrepid friends,” he smiles, still moved by the memory of viewers coming in their droves to support him.

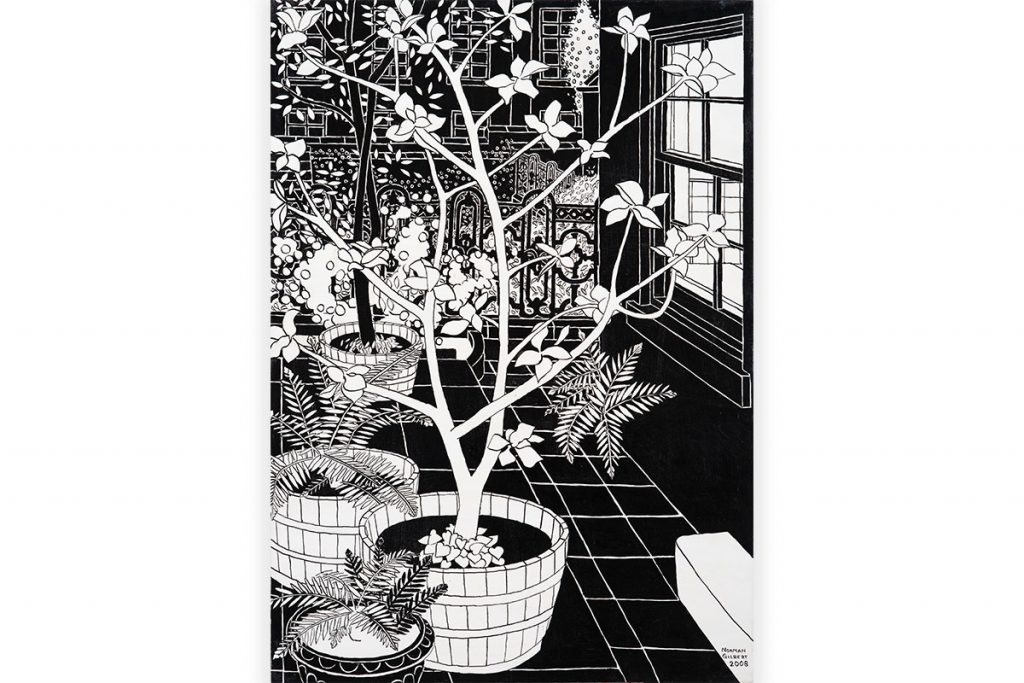

Gilbert has been an artist all his life. His work is meticulous; his creative process stems, he believes, from his teaching days, when he would show schoolchildren how to make linocuts. “I’d tell them that they were trying to get the black Indian ink among the white, and vice versa, and I found myself drawing in this way, working it out in stages and building each picture up,” he explains, motioning to the drawings and canvases propped against the studio walls.

Pat became the breadwinner, happy to let him teach part-time so he could devote himself to painting. Even today, he likes to draw until “the pieces knit together and everything fits, is immovable and in its right place”.

As a child, Gilbert loved drawing. His father was the manager of a sugar factory in Trinidad and the boy was sent home to Troon’s Marr College. “I’d crossed the Atlantic five times by the age of nine,” he smiles, “but I was never happier than when I was in the art room.”

That sentiment remains today. Despite his age, Gilbert shows no signs of slowing down. “The last thing I want to do is stop – it keeps things alive, and each painting I work on has to be better than the last one,” he says. “I have a need to keep painting, and as one painting ends, another one begins. But I have had to teach myself how to work sitting down!”

Norman Gilbert, Passion, Vision and Spirit II, 18 May to 15 June at Tatha Gallery, Fife