If you must make the jump to a more manageable home, it might as well be to a beautiful ultra-efficient new-build – in a corner of your old back garden

Having lived in a large, late-Georgian villa near Arbroath for almost 30 years, the recently retired Graham and Betty McNicol were ready to swap their former manse for a more manageable home. What they were less keen on, though, was leaving a part of the world they’d come to love. Many different possibilities and plots in the local area were examined then dismissed: “We looked at all the options, from buying a house in the nearby village to converting the stables of our old house,” recalls Graham. Nothing was quite right. The manse did, however, have good-sized grounds, including a little paddock, and gradually the idea of using this as the site of a new-build home began to take shape in their minds.

The couple approached a local practice, Colin Smith and Judith Wilson Architects, to discuss their ideas. “We asked them to put together a proposal, and it soon became clear that building a new house in the paddock was feasible,” says Graham.

“We had a few priorities: we didn’t want the new building to fight with the existing house; we didn’t want it to feel like a rabbit hutch – we had in mind a single-storey home with spacious rooms; and we wanted it to be highly energy-efficient and eco-friendly.” They’d come to the right place: the Angus practice specialises in contemporary, energy-conscious design to Passivhaus standard, and creates environmentally aware, low-energy buildings.

The design of the new house emerged out of a period of close collaboration between the couple and Colin Smith. “We worked on lots of ideas for the new house,” acknowledges the project architect. “The driving factor from the very beginning was that it should feel private and separate from the old house. To achieve this, our priority was to keep the roof height low.

“The triangular site, however, was challenging. We decided that the simplest solution was to have a straight, rectangular building with an angled carport connecting into the hall and utility area. This allowed us to allocate more space to the living areas. Even though it appears to be an unusual shape, it’s actually a simple design.”

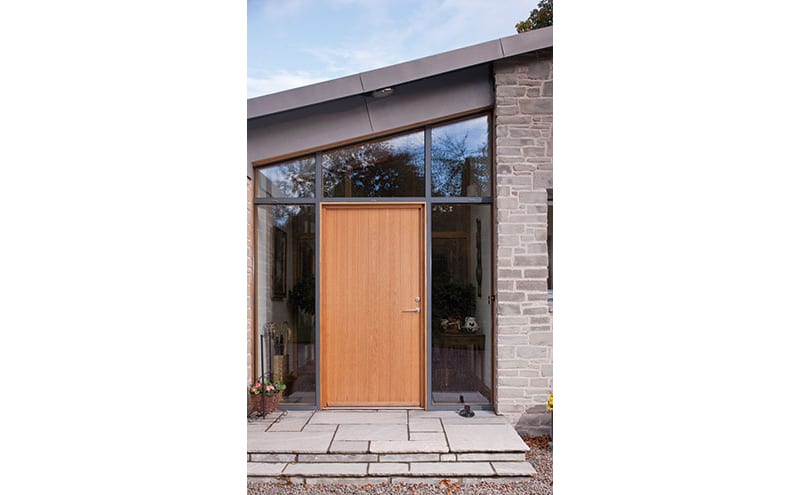

This simplicity is carried through to the palette of materials, which includes zinc on the roof and stone and larch cladding on the façades. Graham is delighted with the way these materials have interacted with the surrounding landscape. “We liked the zinc as it means the house does not dominate – it sits quietly in the landscape and doesn’t demand your attention,” he acknowledges. “It’s the same with the grey sandstone – it tones in with the zinc and blends with the setting. We love the way the silvery-grey colours of the zinc and the stone reflect the beech trees on the adjoining riverbanks.”

The decision to go with larch cladding was down to the clients rather than the architect, as Colin Smith admits: “I hadn’t designed vertical cladding before, and I was a little worried it might look a bit too rustic. But Graham preferred it, and now he has converted us to the idea of it – I think it looks fantastic.”

The project proceeded through the planning process without any hitches; in the meantime, the McNicols arranged for a screen of semi-mature native trees – Scots pine, cedar and birch – to be planted between the Georgian manse and the site of the new house, to give both properties more privacy.

The 48-week-long construction also proceeded largely without a hitch – with the exception of one particular element. “Mistakes were made by the window manufacturer in both the measurements and the production, which delayed our entry by three months,” says Graham. “The hold-up didn’t bother us, as we were still living in the manse, but it was a nuisance for the contractor.”

Apart from the inconvenience, the window delays created a more serious problem, namely how to achieve the exacting standards required for a Passivhaus building. “The missing windows meant that the builders couldn’t do the first air test,” explains the architect. “If you’re building a Passivhaus, an air test is carried out before the plasterboard is put up, as this sorts any gaps out. So the builder had to take a huge gamble and carry on. But it all worked out.”

Much of the reason for this was thanks to Smith’s meticulous prep. “I drew dozens of large-scale details and dimensioned drawings – I left nothing to chance,” he says.

One of the key features of the design is that the house doesn’t have any cold bridging. “It’s triple-glazed and substantially insulated with wood fibre,” says Smith. “It also has a different floor structure to traditional kit houses. With a traditional kit house, the floor goes down to the below-ground blockwork, and then to the foundations. Here, though, it goes straight onto the concrete slab. It’s a completely different concrete slab too, with steel top and bottom, and it’s thicker. There’s also a steel angled grid on top of the roof insulation to strengthen the eaves, which means that the steel isn’t going to cold bridge into the structure of the roof.

“Thanks to its heat exchanger, the house shouldn’t require heating, but underfloor heating throughout, powered by an oil-fired boiler in the shed, was added at the clients’ request.”

Perhaps Graham and Betty simply didn’t believe any building could be comfortable without conventional heating; certainly, since they moved in in 2016, the energy efficient performance of the house has been a revelation. “It’s astonishing – the house maintains a constant temperature of around 21ºC,” says Graham. “The heat exchanger sucks out air from the utility area, bathroom and kitchen, filters it, then restores it to the public rooms and bedrooms. This keeps the temperature even. We do have oil-fired towel rails in the bathroom and shower room, which are set to come on in the morning and evening. But the underfloor heating has barely been used – it just hasn’t been needed.”

The architects put a great deal of thought into the arrangement of the living spaces, eventually placing rooms that aren’t used regularly to the north side of the house, with the more public rooms to the south. The building was also carefully oriented to take advantage of the surrounding views. “This is a particularly pleasant element of the new house,” agrees Graham.

“Many of the main rooms in our old house had double-aspect views over the Angus countryside towards the River Tay and St Andrews beyond, which we enjoyed very much, and this idea has been brought into the new building: the sitting room has dual aspects to the south and west. The architects also managed to squeeze a west-facing window into the south-facing kitchen and dining area, and the master bedroom is also dual aspect, facing south and east.”

From the architect’s point of view, the success of this build is due to the clarity of the design from the layout to the overall form, and the lightness of touch in the detailing. “Proportion is all,” says Smith, “and an enormous amount of effort was invested in that alone. The use of the curved roof and the triangular shape of the site to achieve the shape and height of the entrance is pivotal as you approach and enter the house, giving it the right scale with the minimum of effort.”

The owners couldn’t be happier with the outcome. “This is the first time we’ve built a house from scratch so we approached the project with some trepidation,” says Graham. “But it proved to be a very pleasant experience. We were able to put our own thoughts into it, and I very much enjoyed the collaboration with Colin Smith and Judith Wilson – they gave us their undivided attention.”

He also has high praise for the build team: “Mike Scott, the principal contractor, knew all the sub-contractors and had worked with them on other projects. If we were ever to self-built again, I would ask for all the same guys to come back and work on the project. Not that we have any intention of building again – we are so happy with what we’ve got here.”

DETAILS

What A timber-framed contemporary new-build

Where Near Arbroath, Angus

Architect Colin Smith and Judith Wilson Architects

Photography David Barbour

Words Caroline Ednie