The American architect was a pioneer of postmodernism and won global acclaim the 1980s

words Judy Diamond | photography Courtesy of Michael Graves Architecture and Design

Big hair. Big shoulder pads. Legwarmers. Stonewashed denim. The 1980s, when we look back from today’s viewpoint, was a decade of crimes against fashion.

What were people thinking? It’s a similar feeling when we contemplate what was built at that time, especially in the United States, and especially by Michael Graves.

THE PORTLAND BUILDING, OREGON

One local Oregon newspaper, looking back a few years ago at the Portland Building, one of Graves’s most iconic designs, put it bluntly: it looked like “something designed by a Third World dictator’s mistress’s art-student brother”.

Others were even less kind, informing readers that it was “one of the most hated buildings in America”.

At the time it was unveiled in 1982, however, this chunky office block was regarded as the seminal work of the postmodern movement.

It was unlike anything that had been built before. It took classical elements such as pilasters and corbels and flattened them into bold graphical appliquéd decoration. The bright colours – red, turquoise and blue – made it stand out even more.

A lot of observers hoped it marked the start of a movement that would restore some of the colour and character that had been drained out of American cities by three decades of the featureless, glass-clad International Style, or modernism.

But it wasn’t to be. Graves was the most famous architect of his generation, and although he continued working for many years – indeed, with great success – by the time the 1980s ended his reputation was in decline.

Is it time to reappraise his contribution to modern architecture? Is there more to postmodernism than meets the eye?

His biographer, Ian Volner, believes so: “In recent years, it has come in for a qualified rehabilitation,” he argues in Michael Graves: Design for Life.

“Energies that have long been trained on saving modernist masterworks are now being directed towards postmodernist ones under threat of redevelopment, including a number by Graves himself.”

WHO WAS MICHAEL GRAVES?

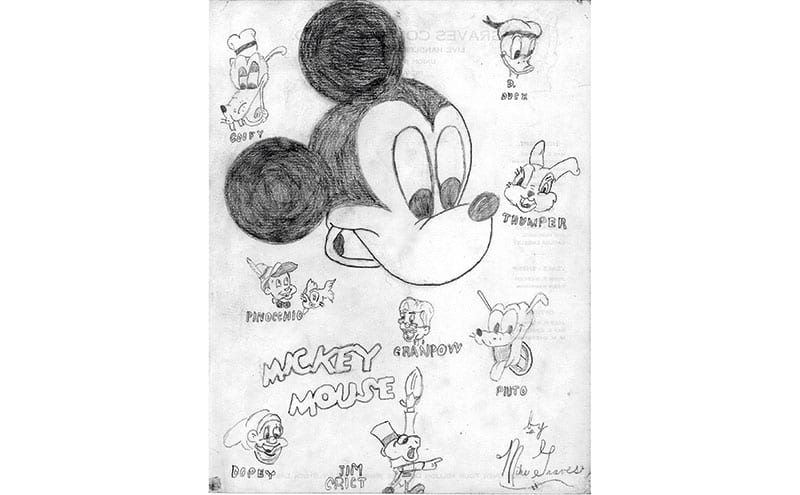

Born in Indianapolis in 1934 the young Michael Graves was a prodigiously talented artist from early childhood.

All he ever wanted to do was draw. His bitter, hard-drinking father wanted the boy to follow him into the livestock trade, but his formidable and resourceful mother could see his promise lay elsewhere, though she was not convinced art was a career.

“Unless you’re as good as Picasso, you’ll starve,” she told him. “What you should do is find work that uses art, but that’s a real profession, like engineering or architecture.”

As Volner recounts in his book, when she described what an engineer does, her son’s mind was made up: “I’ll be an architect.” And that was that.

His professors at Cincinnati were in thrall to the Bauhaus and their perfectly rectilinear structures.

“All the people who were doing modernist architecture were gods,” Graves said later. Their smooth glass-sided slabs and monolithic skyscrapers, however, left him cold. Postgrad study at Harvard was no better, with his tutor ridiculing his interest in the history of architecture.

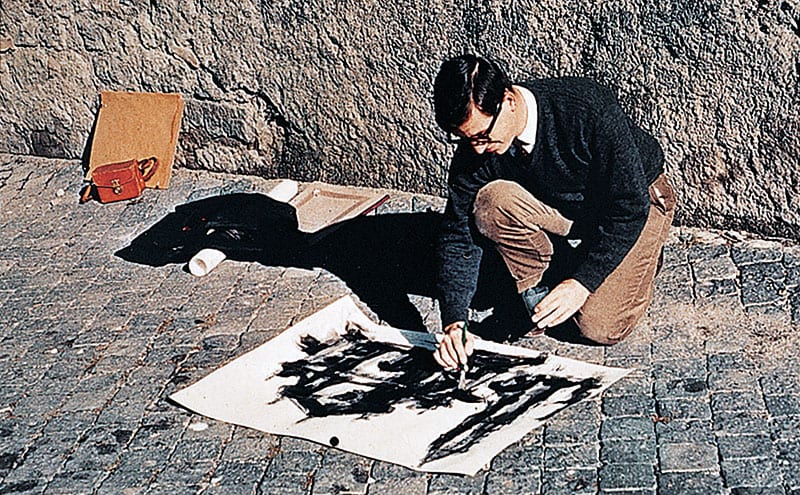

It was only when he won a scholarship to Rome at the age of 26 that he found what he felt was the true purpose and power of architecture: the capacity to communicate.

“His time in Rome had a profound influence on everything that happened after,” said his friend and collaborator Richard Meier.

A NEW PATH FOR ARCHITECTURE

Back in the USA, he wasn’t the only one having doubts about mainstream modernism, and advocating a more dynamic, pop-culture-infused attitude in art and design.

He began teaching at Princeton, with commissions on the side. He joined forces other architects, such as Meier, as one of the New York Five, trying to find a new path for American architecture. And it was while painting a mural for a project by one of the Five, Charles Gwathmey, that things changed for Graves: “A new and unmistakable motif intruded into the composition, not once or twice, but over and over,” says Volner.

“It was a moulding – clearly a response to the crowns of the Beaux Arts buildings visible through the office window. Out of nowhere, mouldings – those humble details derived from the classical cornice but as commonplace as any baseboard in any middle-class living room – were everywhere in his work.”

It was precisely such ‘bourgeois’ decorative details that the Bauhaus architects had rejected. Once Graves had started contradicting modernist ideas, however, he couldn’t stop, and although many of his designs at this time got no further than the drawing board, they were attracting a lot of attention for their exterior ornament, historical references and visual wit.

When the Portland Building was completed in 1982, it thrust the postmodernist movement to the forefront of the design world, and Graves himself to unprecedented international fame.

He continued to experiment, mixing new ideas with traditional forms in order to make a statement or purely to delight the viewer.

DISNEY’S LA HEADQUARTERS DESIGN

He was commissioned to design Disney’s LA headquarters in 1986 and responded with a façade based on a Greek temple, with the Seven Dwarves serving as caryatids.

It felt to some critics like a deliberate provocation, and they were soon dismissing everything he did as mere packaging. Rather than seek to create interiors that improved their users’ lives, they said, Graves’s buildings were all about the façade.

It didn’t help that developers often cut corners and used cheaper materials than he had specified, nor that elements of what had started out as iconoclasm were soon being incorporated into every new shopping mall in suburban America.

Postmodernism began to feel cheap and tacky. The jokes fell flat. It was not the brave new world after all.

It didn’t stop Graves. Commissions continued to pour in from as far afield as Japan and Egypt.

He also had a lucrative sideline designing products for the likes of Target and Black & Decker. His best-known piece was for Alessi, a kettle with a bird on the spout that whistles when the water boils. More than two million have been sold.

In 2003 an infection left him paralysed from the waist down. He kept on working, designing wheelchairs, hospital equipment and even hospitals themselves, as well as prototype houses for wounded soldiers.

He remained inventive and engaged, coming up with new ideas right up until his death at the age of 80.