A radical rethink of how a house should function and what it should look like has produced an award-winning home on the Kyles of Bute

What A refurbished Victorian Cottage

Where Tighnabruaich, Argyll

Architect Technique, in collaboration with Stallan-Brand Architects

Contractor McNee Building Services

Photography Dapple

Words Judy Diamond

Upside down and inside out: that’s what a lot of people feel life is like when they’ve got the builders in. At some point in the future, they hope, the dust will settle and order will be restored. But upside down and inside out actually perfectly describes this home in Argyll, more than a year after its completion and already in receipt of a Glasgow Institute of Architects award. Its living area is on the upper storey, with the sleeping quarters tucked underneath, while the rugged stone walls are insulated outside and left beautifully exposed inside. Both architect and owners are thrilled with its nonconformist layout and rule-breaking finishes.

The house, sitting high on a hillside above the harbour at Tighnabruaich, has been through an almighty transformation. “I’d call it a renovation and conservation project with a twist,” says Jamie Ross, founder of Glasgow-based Technique Architecture and Design. He was commissioned by clients Paul and Seonaid Stallan to turn a couple of dilapidated flats into a single home, maintaining the atmosphere, texture and richness of the stone shell and creating an open-plan living space inside.

Seonaid, an early-education professional and jeweller whose work is made from sea glass found on the shores here, has a long association with this part of the world. “My family first started visiting Tighnabruaich when my grandmother bought the attic flat here in 1967,” she says. “Like the one below it, it was just a room and kitchen with a bed recess and an outside toilet. Both flats were in a Victorian cottage next to a taller building from the same era which was also later sold off as holiday properties – this area was very popular with Glasgow holidaymakers, who’d arrive on the paddle steamer.

“My parents, my brothers and I would spend two weeks every summer in the room and kitchen – it eventually got an indoor bathroom, thankfully. By the time Paul and I were married and had our own children, we’d acquired a second flat, this time in the main building, and continued to spend holidays here with our own children and extended family and friends.

“When the offer to buy the cottage’s ground-floor flat appeared, we saw it as the perfect opportunity for us to create something new and exciting and extend our four-generation connection with the area.”

The stone-built cottage, though, was 150 years old and showing its age. The roof was damaged and the building had a serious dampness problem – the consequence of years of driving rain, an exposed site and little maintenance. “The addition of non-breathable paints to the exterior was accelerating this decay,” recalls Jamie Ross. “Many of the floor joists and lintels and much of the roof structure had rotted and was beyond repair.”

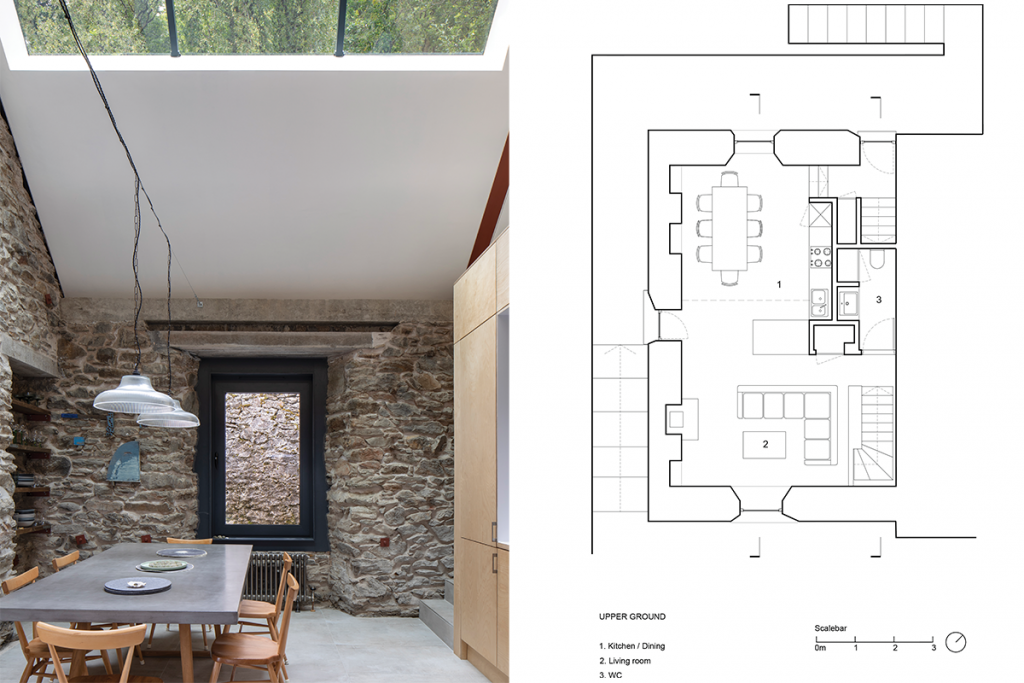

He and Paul Stallan, himself a renowned architect and founder of the Stallan-Brand practice, collaborated on a new and better layout. Arranged across a modest 90 square metres, the reconfigured house is now split over three storeys. The main living, dining and kitchen space is on the upper ground floor, with the en-suite bedroom on the lower ground. The studio and secondary living space are on the mezzanine level, making the most of the exceptional views over the water to Bute.

But it’s the use of materials that really sets this house apart, in particular the original stone. It was worn and weathered and sorely in need of insulation. Rather than follow standard practice and insulate the inner surfaces and then cover this up with plasterboard, the two architects did the opposite, as Ross explains: “Sitting high on the hill, the building is both hard to find and hard to get to. The unique qualities of being both hidden and having an exceptional outlook seemed fitting for a bold design solution as a counterpoint to the conservative Victorian architecture of the town. It was clear from the outset that turning the building inside out and adding an exoskeleton and a ‘jacket’ was the way to do this, while capturing the richness of the existing building internally.”

This jacket consisted of a timber frame, robustly insulated to significantly improve the thermal performance of the house. This was then clad with high-performance powder-coated steel with a textured finish to withstand the harsh marine environment – a long-lasting and very weather-tight design.

Retaining and restoring the original stone was one of the main drivers of the design. Inside, the pointing was painstakingly raked out on all the walls and a new lime mortar was selected to complement it. Birch plywood was used for the kitchen, bath-rooms and storage spaces throughout the house as a hardwearing and sustainable alternative to plasterboard

Rotten timber lintels were replaced with concrete ones and, where new areas and infills were needed on the stonework, a grey engineering brick was used to add to the layers of history.

The form is traditional – apart from the roof: “As we had to rebuild the roof, we took the opportunity to come up with something more sculptural,” says Ross. “Using a steel frame allowed us to have a large asymmetric dormer to the front (a lookout post with incredible views) and expansive rooflight glazing to the rear.”

The footprint is small but this hasn’t stopped the architects achieving a feeling of openness, generosity and light. “To do this, we thought of the stairs, kitchen, bathroom and storage as pieces of furniture within a larger space, rather than as individual rooms,” says Ross. These were designed into what he calls “a sculptural plywood volume” that winds between all three storeys and revolves around the kitchen. “This let us make the best use of the available space and create something of a Tardis.”

It all sounds so simple – yet this was anything but a straightforward project, mainly because of the rural location and the extremely tight site. There was almost nowhere to store materials and not even enough space for a skip. “Materials had to be ordered to arrive just in time,” recalls Ross. “As for the larger lifts of steelwork and rooflights, these had to be carefully orchestrated by the main contractor.”

With the house perched on the hill, surrounded by woodland and other homes, there are very few views of the property. “The day the scaffolding came down to reveal the cladding was a high point – topped only by a fishing trip with Paul Stallan where we both saw the finished house from the water for the first time.

“The inside and outside are so different that it’s difficult to describe them at the same time,” he concludes. “I’d say the outside is shamelessly contemporary. The inside, however, is more nuanced – rich, layered and atmospheric.”

If you’d like to read more of our Architecture features pick up a copy of the magazine, or subscribe here.

Also in our current edition (Sep/Oct 2021):