Part of the Soho avant-garde of the 1950s, he blossomed into a painter of rare emotional intensity

words Catherine Coyle | photography Courtesy of the Estate of William Crozier

His studio is like an autobiography,” recalls the art historian Katharine Crouan of her late husband, William Crozier.

“There were always fresh canvases lined up against the walls – more than he would ever need; tubes of the most expensive continental paints; a new canvas on the easel. All his materials were good to go and Bill approached every new day with this sense of extraordinary optimism.”

Crozier was a true artist. His was a calling, not a job – a compulsion to create that first took hold when he was just a boy, living on Scotland’s west coast.

He was born in 1930 on Dumbarton Road, Glasgow, where his father, Robert, was a plumber at the Govan shipyards. The 1930s were a difficult economic period, and the family moved to Ayrshire where Robert took up a job as foreman at the Ailsa shipyard. It was here, in the seaside town of Troon, that Crozier first began to connect with the vocation that would shape his life.

“His mother, Flora, couldn’t understand his fascination with art,” says Crouan. As a pupil at Marr College, he was already reading the French surrealists and “making himself a nuisance”, but the chair of the school’s board of governors was Alexander Walker – of the Johnnie Walker drinks family, philanthropist and great collector of art (and whose own home was built in the image of Oscar Wilde’s ‘House Beautiful’) – who encouraged the boy’s curious passion for art.

“Bill knew he was going to be an artist,” recounts Crouan.

“He had a great respect for what he did; not just what it is to be an artist but the important position in society that artists have – that was very meaningful to him.”

By 1949, Crozier was at Glasgow School of Art, studying drawing, painting and architecture under the tutelage of Mary and William Armour and David Donaldson.

Prior to his studies, he had revelled in the British Council’s Picasso, Matisse, Van Gogh and Munch exhibitions that had toured to Glasgow’s Kelvingrove. He likened seeing these shows to being “thumped in the solar plexis”, acknowledging their influence and inspiration.

Following graduation, Crozier, who had become friends with fellow Scots painters Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun (the famous ‘two Roberts’), hitched his way to London; there, in Soho, he mixed with poets, bohemians and artists – the very avant-garde of this new scene.

“He became successful early on in his career, but he used to joke that his work went in and out of fashion,” says Crouan.

“He enjoyed sell-out shows in the later 1950s and early 1960s but then made the decision to leave it all behind and move to southern Spain for a year.”

Crozier was not a landscape painter as such; rather, he used the landscape as a vehicle to explore the human condition.

In Franco’s Spain he discovered a different landscape, as well as Moorish and Islamic art, influences that seeped into his oeuvre and remained part of it. This was a productive period for Crozier but when he returned to the UK in 1964, London had changed and he struggled to find his place. He accepted teaching posts and painted theatre sets to supplement his income.

By 1974, he met Crouan at Winchester School of Art where they both taught. “It was around this time that Bill took the surprising step of becoming an Irish citizen,” recalls his wife.

“He’d always felt equal parts Scottish and Irish and, while he detested nationalism, he believed strongly in nationhood.”

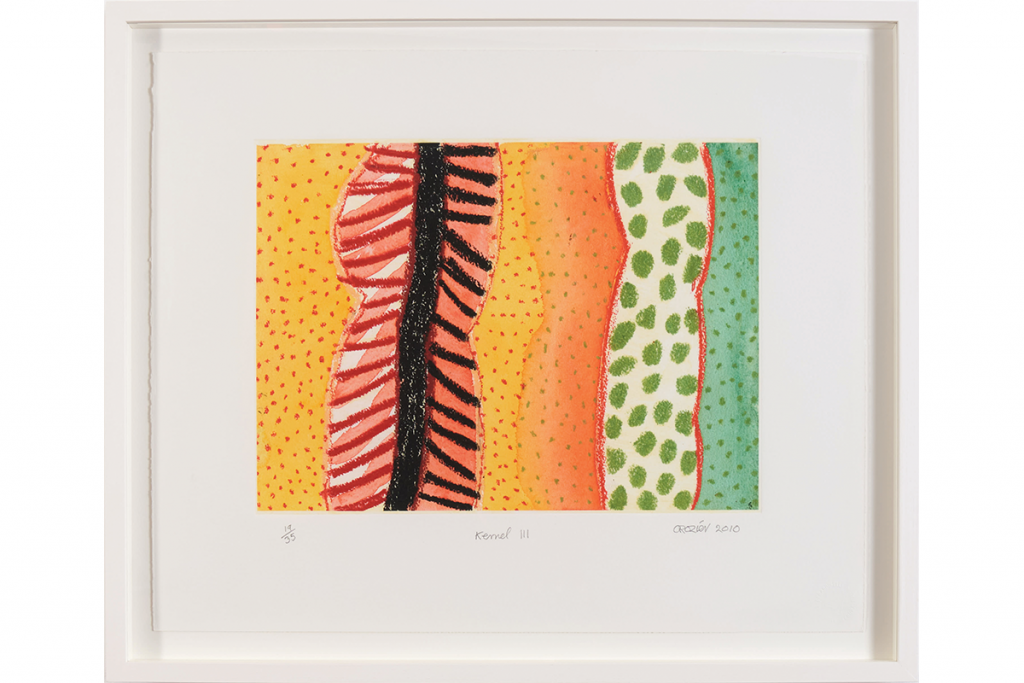

From a cottage in West Cork, Crozier’s art blossomed. Darker elements of his work gave way to the sheer exuberance and exhilaration of colour that he found in the landscape.

“His was always an art of reflection,” says Crouan. “He always looked back, painting in a studio with no windows or with the curtains drawn because he was blotting out the reality of the world outside to give himself space to paint what he had seen and what had left such an indelible impression on him.”

He painted every single day, right up until his death in 2011. In his 80s, during the final few years of his life when he was too sick to make it to his studio, he would paint in his summer house in the garden.

It was important to him to keep going – getting up every day and going to ‘work’. His later works are stripped back, simplified, with anything extraneous taken out, resulting in paintings that have intense clarity of vision and strength.

The Estate of William Crozier is represented by Piano Nobile Gallery, London, and by Flowers Gallery London, New York and Hong Kong; Georgia Stoneman Gallery, London, deals in original prints by the artist