The Orkney-born artist’s radical approach to film is being honoured in her centenary year

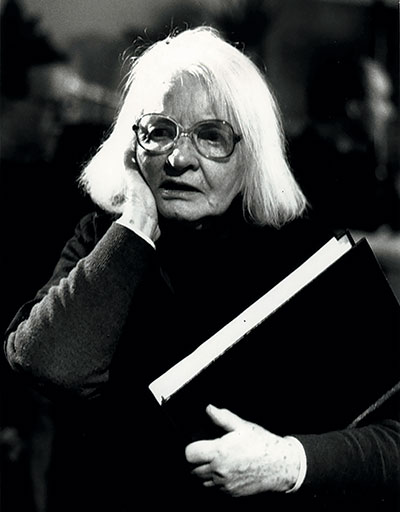

When she opened the 1992 Edinburgh Film Festival with her first full-length feature film, Blue Black Permanent, Margaret Tait was 74 years old.

She had devoted her life to making films, but despite having had some overseas recognition from within filmmaking circles, she was little-known in Scotland. LUX Scotland, the charity that supports artists who work with the moving image, along with Dr Sarah Neely at the University of Stirling, have been trying to put this right.

Over the past year, to celebrate the centenary of her birth, they have put together an impressive programme of events to showcase the breadth of Tait’s talent and to honour her posthumously for her achievements.

Works by the pioneering experimental filmmaker have been on the LUX distribution list since the late 1970s as part of a collection of independent films available to hire and show at festivals or theatres around the world.

But in her home country it was only at the twilight of her career and – as is the case for so many true artists – after her death that there was any real appetite for her work.

Tait was unmoved by this lack of interest, and always refused to compromise her artistic sensibilities. She was the very epitome of the independent filmmaker; if funding was refused, she would press on anyway, self-financing to make her films her way. Over a span of nearly 50 years, she made more than 30 films, every one of which she wrote, directed, edited and produced.

Orkney, particularly the Orkney of her childhood (she was born in Kirkwall to a family of Orcadian sea merchants), has a starring role in her work. Many of her films, including Portrait of Ga and Garden Pieces (the last film she made before her death at the age of 80) were shot there. The islands provided more than just a location, though; the sea, the landscape and the family home are all present in her works, and demonstrate the connection she felt to this part of the world.

Perhaps the toughness of life there at least partly explains the tenacity with which she forged her career. After many years away, she eventually returned to her roots in the mid-1970s.

Tait was sent to school in Edinburgh, where she went on to study medicine. She worked for the Royal Medical Corps during the Second World War, serving in India and Sri Lanka, after which she spent some time travelling. She took up photography and stopped off in Rome, where she went to film school, at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia. Her time in Italy cemented her passion for the moving image and on her return to Edinburgh she worked as a locum doctor to fund her film projects, setting up her own production company to facilitate her work.

Her output was vast, and diverse – as well as making short films and documentaries, she wrote several books of poetry. It could be argued that her films were in fact works of poetry in their own right. The two feel inextricably entwined, the ideas and the expression of her words finding just as much rhythm on screen as they did on paper.

Some describe her as avant-garde, a proponent of ‘pure cinema’ that looks to the elements of vision, movement and rhythm. But she was also a scientist; her methods were exhaustive and this desire to express seemed to override the medium in which she worked. She would hand-paint images directly onto celluloid, beautifully colourful animations that seemed to strip everything back for the viewer, concentrating on just the movements.

Her films, like her poems, are sparse yet rich with life. Her work has an economy about it; there is nothing superfluous. Every assiduously considered frame, every word spoken or note played was planned and captured the way Tait intended. She mostly shot on 16mm film and when each reel was finished, she’d send it to the lab accompanied by extensive notes describing precisely how she wanted it to be processed.

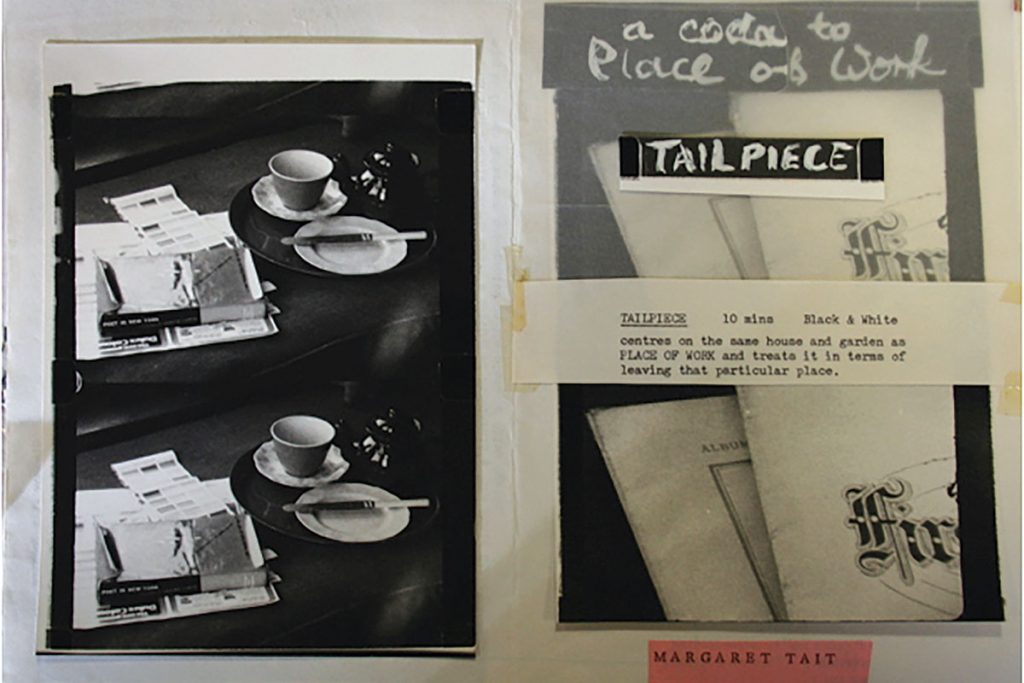

After her death her husband, Alex Pirie, donated her archive of notebooks, storyboards and film reels to the Scottish Screen archive and the National Library of Scotland, where a process of restoration and digital transfer has preserved her work for contemporary audiences to enjoy.

Tait adopted the phrase ‘stalking the image’ from the poet Federico García Lorca. It was as close as she could get to what she had been trying to achieve – “breathing with the camera”, as she described it – a means of capturing the fleeting, unseen moments that define a person or place.

Stalking The Image: Margaret Tait and Her Legacy. Until 5 May 2019, GoMA

Words Catherine Coyle