A collective custom build in Edinburgh has created four bespoke flats in a new eco-friendly tenement

DETAILS

What Four flats in a four-storey tenement

Where Portobello, Edinburgh

Architect John Kinsley

Photography John Reiach

Words Judy Diamond

Building your own home is many people’s ambition, but it’s one that largely remains unfulfilled, forever out of reach not just because of the high cost and complex logistics but because it feels too big and too daunting a prospect to even begin. So instead of living in a home tailored to our own individual lifestyle, we make do and mend in rooms that are too big or too small, in cramped new-builds constructed to minimum standards or in old homes that are draughty and inefficient.

But what if things could be different? What if the self-build burden could be shared with your future neighbours, with all of the cost going into producing a quality building rather than into the pockets of a developer? As the architect John Kinsley has demonstrated in Edinburgh’s Portobello, it’s entirely possible. His project, completed last autumn, created bespoke homes for four families. It is modelled on the traditional tenement, harnessing the best of communal living in what he calls a ‘collective custom build’.

With him leading the way, the project was run by a group of people who shared the building costs and decided upon the layout of each flat to suit themselves. Its success has attracted wide acclaim, and not just from fellow architects; politicians from across the spectrum have been in touch to find out how it was conceived and whether it could serve as a new model for house-building in Scotland.

This kind of collective project might be new here, but it’s well established on the continent, in places like Barcelona, Amsterdam and across Denmark, where it originated. It’s particularly popular in Germany: one in ten new homes in Berlin is constructed by building groups, or Baugruppen. A young, dynamic population willing to initiate and run projects for themselves, combined with a housing shortage and plenty of gap sites, has made the city fertile ground for a new approach to building.

As well as being good value for money, there are social benefits, such as giving the owners a stake in the neighbourhood and bringing them together in shared spaces and gardens. But that’s where any hint of ‘hippy commune’ ends: these are serious, architect-led projects, often funded by specialist lending from green banks.

John Kinsley, who was project architect on the Scottish Parliament, liked the ideas of the Baugruppen, but it was only when he read Lesley Riddoch’s 2013 book, Blossom: What Scotland Needs to Flourish, that it struck him that the traditional Scottish tenement could be the model for communal builds here, particularly if these new homes were energy-efficient and eco-friendly.

To make it happen, he’d need the right site – and he knew just the place. “I used to walk past this vacant lot every day around the corner from my house, and I’d always think what a great site it would make,” says the architect. It was too big and expensive for him to consider as a home for himself, so he’d put it out of his head. Now, though, with the new project in mind, he took another look. A strip of wasteland between a tenement block and a Georgian town-house, it had lain empty for years. A cinema had once stood here, then warehouse, but it was now a muddy eyesore. It was ideal.

In mid-2013 he put a notice on the town website inviting locals to a meeting to explain the concept of a collective custom build. Around twenty people turned up and gave his ideas a very positive reaction. More meetings followed and over the next few months as new people joined and others dropped out, a core group began to form. Legal experts were brought in to work out how they could pool their funds, and, once they were ready to go, the plot was purchased.

“We bought subject to planning approval,” says Kinsley. “The site already had permission for a four-storey residential building, so that was our starting point. But our plans were very fluid at this stage – it was all dependent on what was required.” In this respect it resembled the typical client-architect relationship – the core group effectively became the client and Kinsley as architect tried to figure out the best way to give them what they wanted.

His practice is experienced in eco-friendly design, but here he envisaged an extreme example of this – constructed to Passivhaus standards (supremely well insulated to keep fuel costs to an absolute minimum) and also as a zero-carbon building.

To achieve this, it was constructed from cross-laminated timber panels (CLT), a durable material that allows rapid construction. “The contractor, HM Raitt & Son, didn’t believe me when I said the whole structure would be up in less than two weeks,” recalls Kinsley. “In fact, with a team of just three joiners, it was done in nine days!”

Ideally, as much local material as possible would have been used, but there was no one in Scotland able to supply CLT on such a large scale. In the end it came from Egoin, a Spanish firm with impeccable eco credentials, which manufactured the timber wall and floor panels that were then slotted together on site to form the tenement’s skeleton.

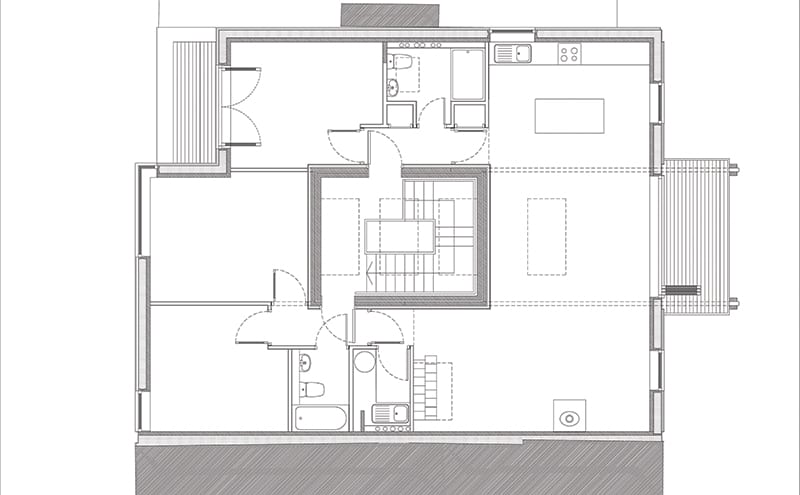

Each floor is a doughnut shape, with the central stairwell core supporting the whole building; it means the positioning of each flat’s internal walls is completely flexible. The exterior was then clad in red sandstone to the front, to match its neighbours, and in zinc to the rear. Triple-glazed windows were sourced from Germany’s Unilux.

“There was definitely an element of making it up as we went along,” admits Kinsley, “partly because it was so new to everyone – including the mortgage lenders and lawyers – and also because the residents’ requirements were still evolving.”

Initially, he had no plans to own one of the flats. He and his wife Jenny, a sculptor and garden designer, were happy in their Georgian house in a neighbouring street, and Jenny in particular had no desire to leave. “I’d spent ten years getting the garden exactly as I wanted it,” she recalls. “There was no way I was leaving – and certainly not for a flat!”

But with the apartment on the top floor available, Kinsley had an idea: how about if the roof was turned into a garden? And when they did the calculations and realised they could sell up, move in here and be mortgage-free, it began to make a lot of sense. (The total cost of the whole project, including plot, building materials and fees, was £1.2 million, split among the four owners.)

There is a communal garden to the rear, and the one on the roof is shared with everyone, but the Kinsleys’ flat has its own special access to it via an ingenious internal staircase that doubles as storage space, one side open to the living area and the other to the utility room.

It’s this kind of personalisation that has made the flats such a success for their owners. To keep costs down, it was up to each family to choose their own bathroom fittings and kitchen; for the latter, the Kinsleys specified beautifully pared-back cabinetry by Birkwood, a Perthshire firm that specialises in plywood. It sits at one end of the light-filled open-plan living space, with a sitting area at the other.

There are three bedrooms, two of which are occupied by the couple’s student sons. “Their rooms and bathroom are in one corner of the building and can be accessed via their own front door – they could feasibly be split off to form a separate flat,” says Kinsley. “It’s the same on all four levels. We’re here for the long haul but it gives us flexibility to change things in the years to come.”

Built to last, drawing on the past but looking firmly ahead: it’s exciting to think this really could be the future for Scotland’s homes.