The life and work of the controversial American architect is the subject of a lavish new monograph

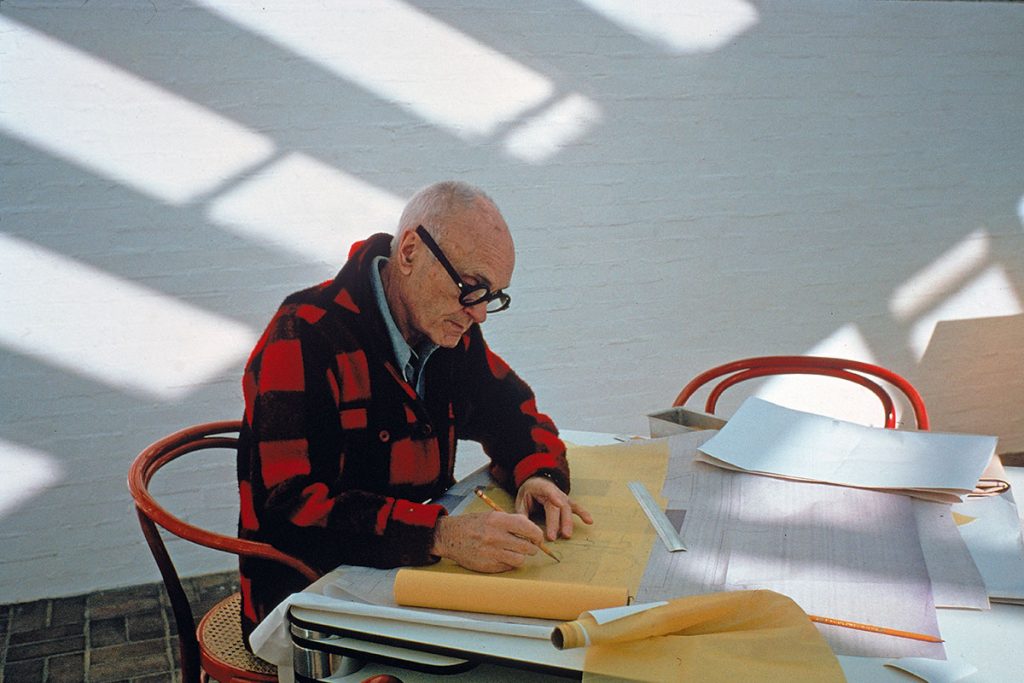

Philip Johnson would have felt right at home in 2020. The advent of social media and our celebrity-driven culture would have made his eyes light up, and he would have relished the endless opportunities to reinvent himself; although he is regarded by many as one of the most significant American architects of the 20th century, Johnson’s greatest talent lay not in his design skills, but in his ability to find new ways of staying at the forefront of the cultural landscape. Had he been alive today, in our interconnected digital age, there’s little doubt this flamboyant, controversial maverick would have been vying for the position of America’s greatest social media influencer.

A new book, Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography, published by Phaidon this spring, takes an in-depth look at the self-confessed chameleon’s oeuvre. Author Ian Volner addresses the various roles Johnson adopted throughout his life – architect, politician, collector – and shows just how nimbly he responded to the changing face of the United States. His was a career based on connection, on exploiting opportunities and always staying ahead of the curve.

Johnson was born in 1906 in Cleveland, Ohio, into a wealthy and respected family. He went to Harvard but his years as an undergrad were not happy ones; while he never denied his homosexuality, it was illegal to be gay in the 1920s. He also struggled with a bipolar disorder and found it difficult to maintain friendships, not really fitting into any particular college crowd.

He had already travelled widely before he graduated, but once he completed his studies in 1927 he took off on a series of European adventures. It was good timing for anyone interested in architecture: he was introduced to the work of Bauhaus director Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, with whom he would subsequently collaborate on the Seagram Building in Manhattan. He was inspired by what he found and loved the newness of this group’s creations; in his job as a curator at MoMA in 1930, he became a tastemaker, promoting their work to an American audience.

He later returned to Harvard to complete his own architecture studies, and would go on to become very successful in his field, designing some of the most recognisable buildings in America and winning the inaugural Pritzker Prize in 1979. In the 1930s, however, his mind was on darker matters and he became involved with fascism. He was a frequent visitor to Germany during this period and even attended Nazi rallies, admitting to getting ‘swept up’ in the ‘spectacle’ – ironic, given that the Bauhaus approach to teaching and creativity was despised by the Nazis, and that Mies and Gropius would be forced to flee to the States as the situation in Europe deteriorated.

Johnson was drafted into the US army in 1943 and set up his own architecture practice in New York on his return. In subsequent years, he made attempts to repair his reputation as a Nazi sympathiser, not least by promoting Jewish architects and building a synagogue free of charge. The FBI, perhaps unconvinced, kept a file open on him for many years.

There’s no doubt Johnson was a skilled designer, but his success also owed much his ability to charm and network, gossip and sweet-talk. And he was always eyeing up his next commission. “I’m a whore,” he once said in an interview, “and I am paid very well for building high-rise buildings.”

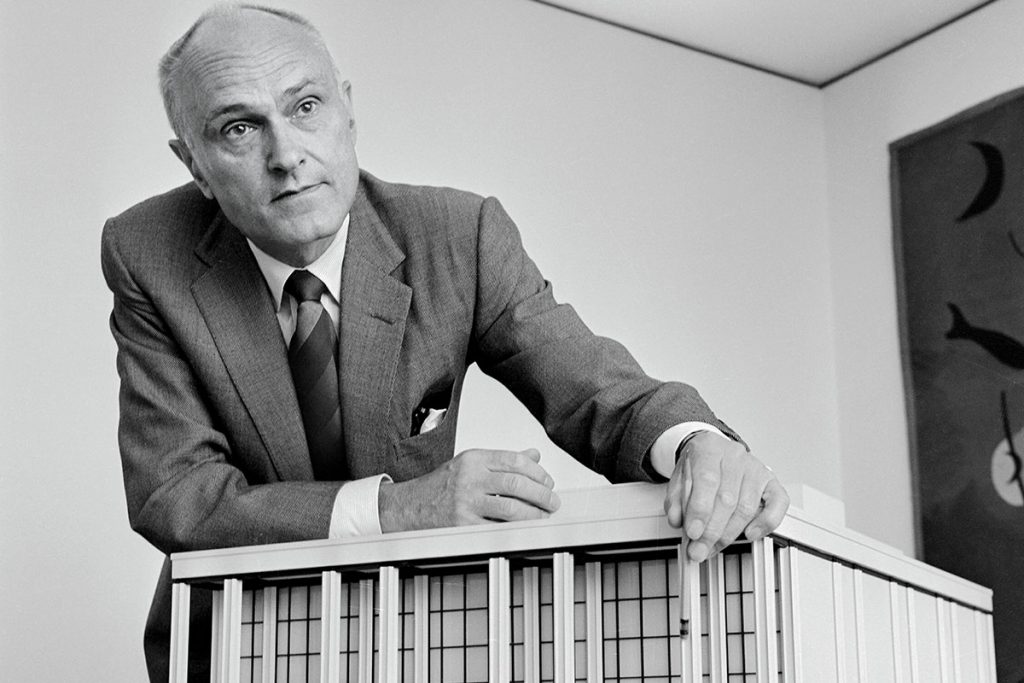

During the 1980s, by now working in partnership with architect John Burgee, Johnson’s portfolio did indeed seem to concentrate on skyscrapers, embracing a form of postmodernism that he’d previously denounced. Money, power and notoriety appear to have become his principal motivations, and in his later years most of his work was for big business and billionaires, Donald Trump among them.

The shimmering towers of Manhattan, Dallas, Houston and many other cities remain as a testament to Johnson’s influence, but even now, 15 years after his death, there is no consensus about his contribution to architecture. His buildings have as many critics as admirers, and it’s hard to discern any single style or common thread in his work beyond the pursuit of status and power. “I guess,” he once said, “I want to make money, just like other people. Perhaps more than other people.”

Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography by Ian Volner (£100, Phaidon) is published on 29 April