His country houses delighted his Edwardian clients and are still ranked among Britain’s best-loved buildings

Behind every great man, so the old saying goes, there is a great woman. In the case of Sir Edwin Lutyens, one of Britain’s most successful, prolific and celebrated architects, there were several. His contribution to the architectural landscape both in the UK and further afield should not be underestimated, but had he not forged strong and prosperous relationships with the women in his life, his career could have taken an altogether different route.

Edwin Lutyens was one of thirteen children born to Charles and Mary Lutyens. Both maternal and paternal lines came from a military background, and his father only took up painting once he had retired from the Forces. As a child, Lutyens (affectionately referred to as ‘Ned’) suffered ill-health and so was home-schooled, spending much of his time in the company of his mother.

At home in Surrey, he spent long hours sketching, and by the time he was a young teenager he was considered to have a genuine talent for drawing. The family’s neighbour was the artist Randolph Caldecott, who took the boy under his wing and helped him to hone his skills.

Lutyens’ daughter Mary, in an essay on her father in 1981, recalled his love of sketching: “He would take with him on all his walks a small pane of clear glass, a penknife and some pieces of soap sharpened to fine points,” she wrote. “He would look at some portion of a building through the glass and trace what he saw with the soap. Cleaned with a damp rag, this ‘sketchbook’ would serve him over and over again.”

His family could see that his love of country houses and aptitude for drawing pointed to a career in architecture. He was enrolled in the South Kensington school of architecture at 16, where he studied for two years, before taking up a role at the prestigious practice of Ernest George. There, his most lucrative and long-lasting partnership was formed when he met Gertrude Jekyll, an artist and photographer who had turned to garden design, and who provided for Lutyens a seemingly endless flow of commissions to create the country homes of the Edwardian elite.

Lutyens and Jekyll complemented one another; although she was 25 years his senior, the partnership flourished, with his Arts & Crafts style working in harmony with her avant-garde landscape design. Between them, they took the notion of a country house, a place where wealthy families and socialites would retreat at the weekends to entertain, and gave it bona fide standing within the canon of British architecture.

As well as being adept at identifying commissions that would give them both an outlet (and an income) for their creativity, Jekyll was exceptionally well connected and opened up new social circles to Lutyens. Together, they were able to create links between buildings and their surroundings, treating the garden as an extension of the house as opposed to a separate entity.

The pair’s link with Country Life magazine was also a rewarding one, thanks to the media exposure and the endorsement of its highbrow editor, Edward Hudson – he had Lutyens work on his own properties, and this vote of confidence in the young architect’s abilities proved pivotal to his success.

It was also through his well-connected friends that he met his future wife, Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton, daughter of the Earl of Lytton. Her family, like Hudson and Jekyll, proved to be an inexhaustible source of work, with commissions keeping Lutyens so busy he didn’t have time to sit any professional architecture exams. Of course, timing was on his side; he was able to take full advantage of the Edwardian desire for status symbols.

In Scotland, he is known for two buildings, both of which possess the architectural elements that became synonymous with his name. His work on altering the Ferry Inn, on the Rosneath peninsula near Helensburgh, was commissioned by Queen Victoria’s daughter Princess Louise, herself a talented artist who knew Gertrude Jekyll.

Lutyens, then 27, extended the old inn in 1896, bringing the property closer to the water and drawing its inhabitants out to the incredible views across Gare Loch to the Firth of Clyde. The balance found in the main entrance, coupled with the addition of the grand chimney (an awe-inspiring structure in itself) that acts almost as a bridge between the different levels and elevations, shows Lutyens’ commitment to the Arts and Crafts style.

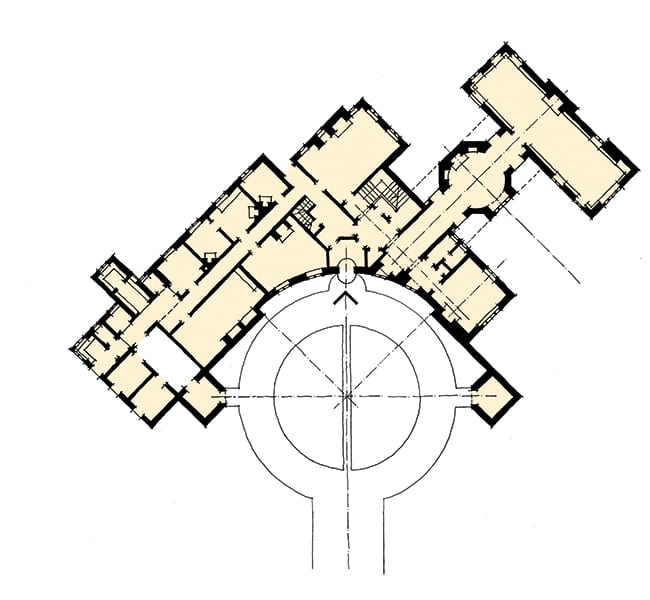

At Greywalls in East Lothian in 1901, he tackled his only other Scottish commission with the same level of maturity and assured elegance. Considered by many critics, contemporaries and fans as one of his finest houses, he designed Greywalls for Alfred Lyttelton as a ‘house in the country’ where he could retreat to play golf. Lutyens’ aptitude for geometry can be seen in its effortless symmetry and balance, while the discreet way he directs the inhabitants towards the views beyond the windows showed the painstaking care he took in his work.

Following the upheaval and social change ushered in by the First World War, demand for country houses declined and Lutyens’ golden period was over. He continued to work, designing the Cenotaph in Whitehall, for example, and planning the city of New Delhi in India, but it’s his Arts & Crafts houses that he is still best loved for today.

Sir Edwin Lutyens: The Arts & Crafts Houses, written by David Cole (Images Publishing) is out now.

Words Catherine Coyle