The Scottish painter was first inspired to take up art while a prisoner-of-war in Colditz Castle

words Catherine Coyle | photography Courtesy of Lady Haig Paintings copyright The Artist, courtesy of The Scottish Gallery

It was only really towards the end of his life that Earl Haig was able to step out of his father’s shadow and make his own impact.

George Alexander Eugene Douglas Haig – known to friends and family as Dawyck – was the second Earl Haig, having inherited the title at the age of nine on the death of his father, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, in 1928.

The Field Marshal had been a senior commander during the First World War and had led attacks at Passchendaele and the Somme; in the decades that followed many blamed him for the colossal casualties, and for a time he was nicknamed Butcher Haig.

It proved a difficult tag to shake off. But the younger Haig’s loyalty was unfaltering, and much of his life was dedicated to defending his father’s reputation.

While he was later able to carve out a career of his own as a successful artist, the pressure to protect the family name took precedence, and it is perhaps only posthumously that his personal achievements have been recognised in their own right.

WHO WAS EARL HAIG?

Haig was the third of four siblings, and the only boy. The family home at Bemersyde, near Melrose in the Borders, had been bought by ‘a grateful nation’ in appreciation of his father’s military service.

He suffered from ill-health as a child but was sent to prep school in Edinburgh, and from there to public school at Stowe, where he flourished.

He proceeded to Christ Church, Oxford, but by 1939, he’d signed up to the Royal Scots Greys. When his brigade was surrounded in the Western Desert in 1942 he was captured, presumed dead.

It was this brush with death that prompted him to take up art.

ART IN THE FACE OF WAR

Having been sent to prisoner-of-war camps in Italy initially, he was transferred to Colditz Castle; there, he was one of a group of prisoners – dubbed the ‘prominente’ – whose lives were spared by Hitler due to their connections.

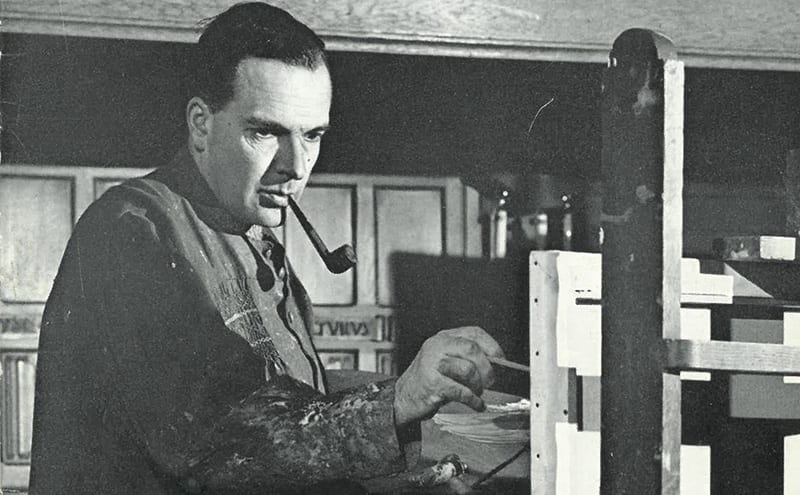

Haig described the prisoners as “escapists, administrators, sleepers, students or creators”, admitting that he combined the latter two categories, focusing on painting to occupy himself during incarceration.

He read books on art, took up painting and completed several portraits during his time there, and his first exhibition at the Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh in 1945 included some of works from that period.

After the war, and buoyed by what he had created during his time in captivity, Haig decided to study at Camberwell Art College.

It was here that he was exposed to some of Britain’s great realist painters and was tutored by greats such as Victor Pasmore, William Coldstream and William Johnstone among others.

With mentors and contemporaries broadening his artistic view, Haig was energised; he developed his work, explored new styles and revelled in this new group of exciting and influential friends.

The military tradition in his family has been eclipsed by his desire to become a painter.

He was prolific during this period and mounted shows in London at the Redfern Gallery and at the Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh.

There is little doubt that Scotland, and the Borders in particular, where Bemersyde Estate enjoyed 1,500 acres of countryside by the River Tweed, became integral to his work.

THE LIFE AND DEATH OF EARL HAIG

He married fellow artist Adrienne Morley in 1956 and had three children, but the relationship ended in divorce.

He married for a second time, in 1981, to an Italian, Donna Gerolama Lopez y Royo di Taurisano, affectionately known as Fruzzy, with whom he travelled extensively.

While the 1960s brought a period of experimentation, there was a gap in his artistic journey that didn’t really gather pace again until the late 1970s.

His travels with Fruzzy saw him make watercolours and pen drawings – preliminary sketches that were often worked up into oil paintings back at his Bemersyde studio. His work grew freer and his style became more defined, confident and at ease.

In a newspaper interview in 2003 he remarked, “I’m not really bothered by what people think about my paintings unless they are people who have a deep knowledge of art; but everyone likes to feel they are appreciated by others, that their work will be of a quality to be preserved for the future. But do I paint for myself or for others? I just paint because I have to… and I want to go on as long as I can.”

He managed to continue, exhibiting at his 90th birthday show, before his death the following year, in 2009.

The Scottish Gallery staged a memorial exhibition of his work, and in his centenary year, showed more of his paintings. The gallery’s 65-year relationship with the painter has helped to raise the profile of an important Scottish artist whose legacy should be liberated for all to enjoy.