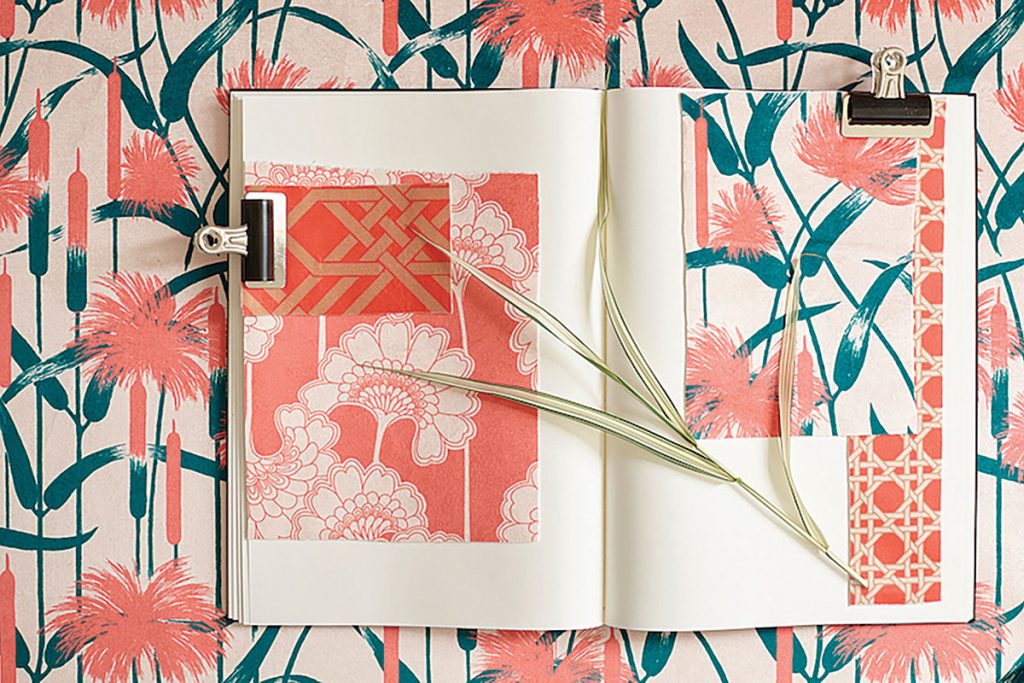

Colourful, fantastical textile designs reflect the complex character who created them

Ask a child what they want to be when they grow up and the replies tend to be pretty standard: footballer, scientist, vet. On the odd occasion, you might get an artisan baker or an aerial yoga instructor.

If you’re anything like Florence Broadhurst was, though, you’ll live out your most elaborate childhood fantasies and stun everyone into silence with your originality.

Born on a cattle station in the inhospitable Australian outback in 1899, Broadhurst took on as many different guises as she could during her life.

She was no Walter Mitty, though; she fully inhabited every one of her roles, however fanciful, executing them with aplomb.

Her parents were poor but ambitious and made sure their daughter had music lessons. She grew up to be an accomplished singer and, by the 1920s, had joined a vaudeville troop and was travelling across the Far East under her new name of Bobby Broadhurst.

On reaching Shanghai, this sociable and vibrant young woman set up the Broadhurst Academy, a finishing school for the children of wealthy expats. She was 26, armed with self-belief and seemingly unstoppable PR prowess, and she quickly made a success of this venture.

Alas, her timing was poor, as Helen O’Neill, author of Florence Broadhurst: Her Secret and Extraordinary Lives, explains. “Colonial Shanghai was crumbling and the Massacre of 1927 forced her to move on, heading this time to London’s Bond Street, where she reinvented herself as a French couturier named Madame Pellier, selling her designs to debutantes, aristocrats and the theatre set.

“She wasn’t a spy but she lived like one,” says O’Neill. “Each time she took on a new persona, she did so for business reasons – a bit like Madonna!”

The Second World War brought Broadhurst back to Australia, this time in the guise of an English aristocrat. By this point, her first marriage had fallen apart and she was in a relationship with Leonard Lloyd-Lewis, an engineer with whom she had a son, Robert. She kept up her fictitious persona, persuading people that she was friends with Winston Churchill and had links to the royal family. When Lloyd-Lewis left her for another woman, she had to think up new ways to make money to support herself and Robert.

After a stint painting portraits of wealthy Australians, she was networking at top-level fundraising events when Broadhurst identified a new avenue that she could exploit. “She was a PR genius,” believes O’Neill. “She was approaching 60 and starting over, but she could see that there was a market here for her: she proclaimed herself to be the designer that Australia had never had before.”

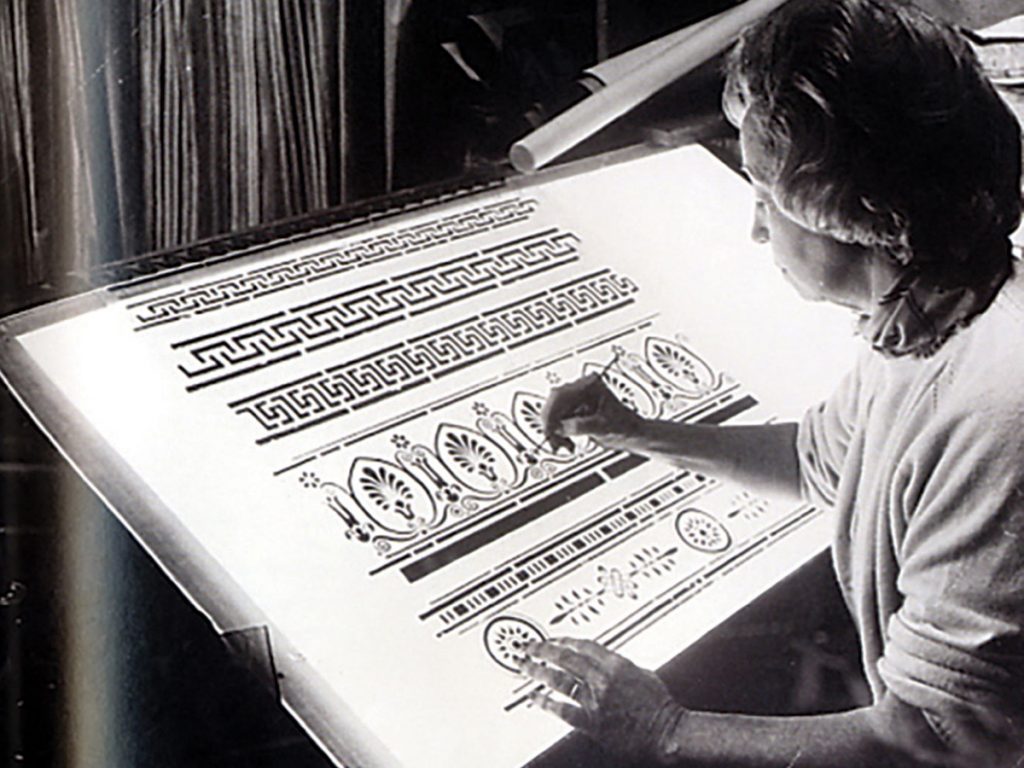

Borrowing a book about design, and working with a tenant of hers who happened to be a wallpaper designer, Broadhurst taught herself the fundamentals of design, drawing on her travels and her glamorous lifestyle to inform her first collection. Her portfolio expanded from that point on, and she created more than 500 patterns for fabrics and wallpapers.

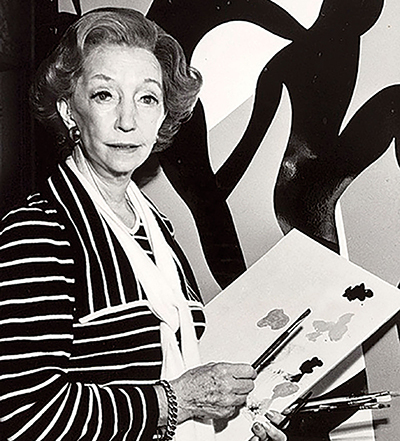

That figure is likely to rise, as more examples of her work are being uncovered as her story reaches a contemporary audience. “She was a hurricane,” agrees O’Neill. “People didn’t know what to make of her. Even into her 70s, she was a party animal, with her dyed bright red hair and flamboyant outfits.”

A life this extraordinary was never going to have a quiet ending: and, tragically, in 1977, Broadhurst was murdered in her studio. She was 78. It is believed she had befriended a serial killer known as ‘the granny killer’. Many of the details of the crime matched the murderer’s profile but, without enough evidence to bring her case to court, her death remains unsolved to this day.

Reviving Broadhurst’s archive has been almost as dramatic as its creator’s life; her designs, drawings and silk screens were saved from destruction on several occasions, and have now been reissued in the UK by Rebecca Lawrence, Carole Spink and Jane Martin, with 61 wallpapers and 23 fabrics available.

“Florence was an extraordinary character and her legacy, the archive, is a fascinating and diverse source of amazing designs,” says Rebecca Lawrence.

“After a decade or so of minimalism, the interiors world is seeing a revival of colour and pattern, and Florence’s work feels so relevant again. Her incredible designs deserve a new spotlight.”