A far-flung corner of Argyll is home to a new-build with sublime views all round

DETAILS

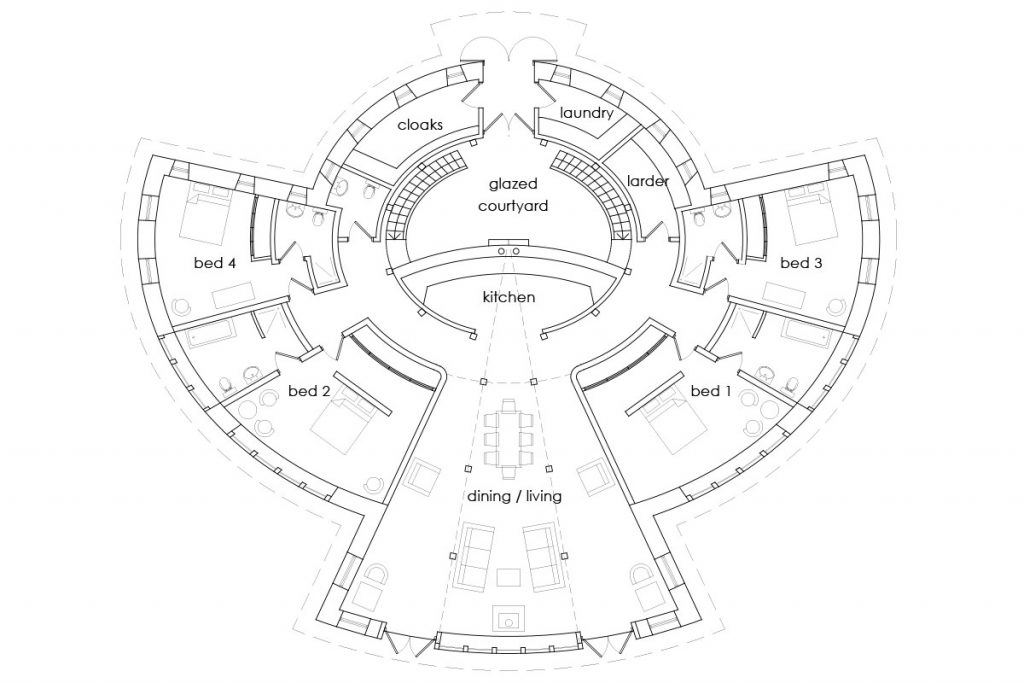

What A circular new-build with four bedrooms

Where Sound of Mull, Argyll

Architect Roderick James

Photography Nigel Rigden and Mark Nicholson

Words Catherine Coyle

Roderick James first came to Argyll in the mid-1990s to design a home for the former owner of the Drimnin estate. The architect, a boating enthusiast, fell in love with the area, so much so that he kept coming back and the west coast became his favourite spot for sailing. It wasn’t long before he and his wife Amanda Markham decided to make the leap from holidaymakers to locals and set up home on the Morvern peninsula.

Then, in 2007, when Roderick James Architects LLP was commissioned to create a development of 21 homes on the neighbouring Ardtornish estate, the couple jumped at the chance to kick-start the project, buying the first plot themselves. “Our plan was to build a property that we’d then rent out as holiday accommodation,” says the architect. “But we ended up loving it so much that we decided to live here ourselves.”

It’s easy to see what won them over. The spectacular spot rises from the hillside like an eagle swooping over the water. The location – overlooking the Sound of Mull in this remote corner of Argyll – is breathtaking, and the uniqueness of the site inspired James to design something very special indeed. It’s far from showy, though: “When you’re out on the water,” he says, “the house is almost invisible thanks to its turf roof and its shape. It takes on the form of the hillside. It’s very discreet.”

When you do see it, of course, the circular building is quite remarkable: “It has an organic shape – there aren’t really any straight walls,” says the architect. “It was designed that way because we wanted it to be the kind of place where people can come together.”

Informality and this sense of togetherness were the driving forces behind the concept, resulting in easy-going, open spaces and a distinct lack of corridors. “We liked the idea of having different places in the house, so people could have their own space but not feel shut away,” explains the architect. “You’re connected, even though it’s a big house.”

Its incredible curved shape derives from the elliptical glazed roof and from the desire to maximise the 270-degree views of the Sound of Mull. From the entrance on the north side, a weighty oak door leads into a glazed courtyard and the eye is drawn up to the open structure above.

Looking a bit like an observation deck, this upstairs gallery is open and bathed in natural light from the glazing overhead. It acts as the central point around which a traditional Scottish broch-style structure has been fashioned.

By creating very thick, curved walls around the outer edge, essential services such as the pantry, laundry, boot room and so on have been concealed between the outer structure and the central open living quarters. There is also symmetry in the footprint, with four en-suite bedrooms on the ground floor off the main living area that faces the ocean views.

Beyond the courtyard is the kitchen, which in turn opens to the dining and living areas. As much of the Douglas fir Glulam frame has been left exposed as possible, the beauty of the wood lending a warmth to the interior. It’s complemented by gentle wainscoting and a pale lime-washed wood finish.

Curved stone walls have been coated in a textured plaster that gives a raw lustre; James believes this lends itself to the relaxed atmosphere of the main living room. “It’s very big but it’s an easy house to inhabit,” he says. Markham agrees: “It’s like a modern-day country house but without the formality.”

While the house has been designed to harness those incredible views, there’s plenty to hold the attention inside. The kitchen has been laid out like a stage, facing the main living room, although there is the option of closing a partition to create privacy if required. From that same central space, you can see across to the upper floor. There, a cinema projector encourages you to relax but, thanks to the open deck, still feel part of the one room.

Along with capitalising on the location, James’s primary concern was to make the house as environmentally friendly and efficient as possible. “In terms of energy, this place costs nothing to run,” he says. “We installed 450mm-thick recycled newspaper insulation in the walls and roof, plus 15kW of photovoltaic panels that generate electricity for our lighting and heating, resulting in no electricity costs.”

The Velfac windows are triple-glazed, and an air-source heat pump has been fitted, which allows pipes to be laid very close together (around 100mm apart) under the floor, with the excess heat being stored in a thick concrete layer beneath the wooden flooring.

Two woodburners – a Scan stove in the living room and a Clearview stove in the courtyard – add to the ambience and help make the place cosy in winter when additional heating might be required. Lake District limestone on the living area floor provides texture among the neutral scheme.

Although statement pieces have been chosen for the interior, such as the Timothy Oulton-style furniture in the courtyard (made by a carpenter in India and shipped directly to Argyll), the house is designed to be used comfortably and confidently. This is a building that, despite its unusual form, never takes itself too seriously.

“I think architecture should be playful,” says James. To that end, each of the en-suite bedrooms is gently themed – adventure, fishing, and so on; the Post Room (so-called because it contains a vintage American postal desk with doocots displaying the decoys James carves by hand) has furniture facing out towards the French doors that lead to the deck, framing the wild seascapes beyond.

When the sun goes down and the soft light from the burners casts a hazy glow, the building feels like a lighthouse or a ship docked on the still waters, waiting for morning when the true glory of its majestic form can be appreciated in daylight. “This part of Scotland is just amazing,” says the smitten architect.