When James Ogilvy and his family moved into their new home in the East Neuk of Fife in 1991, the garden was in a sorry state. The house itself was little better: a one-time summer home built in the late 18th century for a Dundee merchant, Coates House could most kindly be described as a ‘doer upper’. Undaunted, Ogilvy and his wife Julia and their two children had fallen for the place and its breathtaking views; the garden, around an acre and a half of land, was an ‘extra’ that he didn’t realise would become career-defining.

At that point, Ogilvy was working from home, running his own publishing company, and was able to venture outside often to start tidying up the more over-grown and bedraggled parts of the grounds. “I knew nothing at all about gardening,” he recalls. “I was just trying to smarten the place up.”

Today, 28 years on, things are very different. He gradually discovered that the more he did to the garden, the more interested he became in it. He talked to the owners of neighbouring properties about what they were growing and what was thriving on their land, and he read lots of books on the subject. “I really built it up over a long period of time,” he says. “Ninety per cent of what you see today was done by me and a spade, so it was certainly a labour of love.”

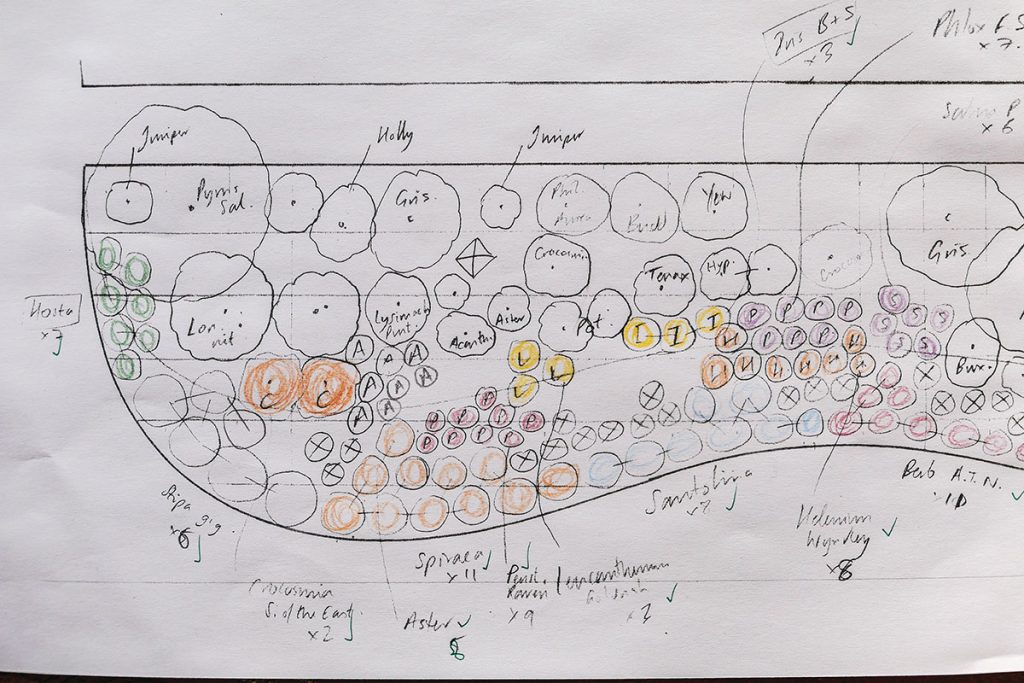

In fact, Ogilvy has now changed careers, having retrained and qualified as a landscape designer (as well as a professional photographer), undertaking a landscaping course at London’s Inchbald School of Design five years ago. “I already had loads of practical experience, of course, but the course (which I did part-time and remotely) taught me techniques such as technical drawing.”

For his own garden – and, indeed, for his clients’ projects both in the UK and the US – the most important element is the structure, he believes. “You don’t often dig up the whole garden,” he admits. “Here, I worked around the history of the place.” A revealing set of ‘before’ images shows that one of its distinguishing features had been a commanding row of cypress trees. These collapsed but Ogilvy wanted to keep the lines they’d created, to give definition to this part of the grounds.

In keeping with the Georgian country house which it surrounds, the garden embraces a number of classical elements, such as formal sections of planting and a well-manicured lawn, but there are also more relaxed areas that are better suited to modern family life. “I added beds to form the shape of the lawn and the meadow and, bit by bit, I planted the birch trees and the roses and added the stainless steel pergolas.”

The garden is in an open position, just a mile from the sea, and looks down towards the Firth of Forth. As a result, it’s usually buffeted by a strong westerly wind and Ogilvy had to be mindful to plant robust species with sufficient foliage and structure to provide shelter.

The lawn was originally laid out to give his young children a place to kick a ball, with small borders containing shrubs and easily maintained plants such as Spiraea, Santolina and Hebe. A cute reclaimed sailing boat fashioned into a kids’ treehouse nestles magically in a vastly overgown Griselinia shrub; this is in the meadow, where grasses are longer and flowers are wild and colourful, requiring less attention and providing a rambling, unfussy fairy garden for kids to take full advantage of. It also encourages wildlife.

There’s a neighbouring adults’ summer house too, which has been encased in New England shingles (Ogilvy and his wife Julia have been summering in Cape Cod for many years) and the space is designed to be both visually impressive and completely functional. The terrace shows off these two purposes to good effect; originally a tarmacked area that visitors used as a car park, Ogilvy took a pick-axe to it and single-handedly transformed it into a relaxed, well-used spot in the garden. “Once I’d gotten rid of the tarmac, I put in box hedging, lavender and roses,” he recalls. His hard graft paid dividends: “It’s a great link between the house and the garden, with seats, fragrant plants and lots of herbs.”

To the right of the meadow is a smaller hedged kitchen garden and, beyond that, voluminous trees and bushes bearing apples, gooseberries and raspberries. “I’ve tried to create ‘rooms’ in the garden,” explains Ogilvy, who says that his work here has been an organic process over a long period of time. Even now, in what he describes as their mature garden, change continues. “The work is never done,” he smiles. One harsh winter can destroy months of labour, killing plants and taking him back to the drawing board.

But that, he says, is part and parcel of the job. “You learn every day, wherever you are. In New England, garden landscaping has a more defined design aesthetic. Gardens are more monochromatic as a result of the climate. It’s an endless process but that’s what makes it so fascinating.”