A focus on people rather than aesthetics set the Vienna-born designer against most of his peers, but his radical ideas are increasingly finding favour today

As Victor Papanek was writing Designs for the Real World in 1971, he had no idea it would become one of the most widely read books on design ever published. At the heart of his text, and indeed his practice, is a commitment to use design as a platform to improve people’s lives. Today, two decades after his death, as consumerism runs riot, the gap between rich and poor continues to grow and the world is gripped by social and environmental uncertainty, the words of this Austrian-born designer, activist and educator seem more relevant than ever.

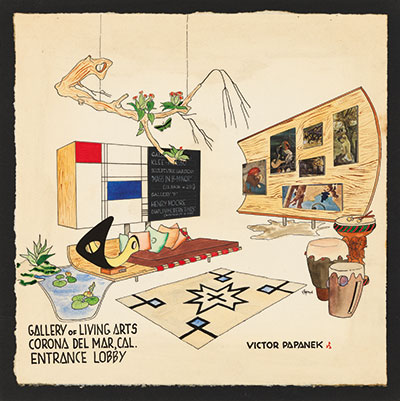

Papanek’s take on design was always democratic; it was a conduit for him to tackle world issues and a means of exploring methods of sustainability and equality through radical yet deeply practical ideas. “The only important thing about design is how it relates to people,” he said. The Vitra Design Museum’s current retrospective is the first time that his work has been exhibited so extensively, and includes manuscripts, objects and drawings that have never been shown in public before.

Alison Clarke, professor of Design History, and Director of the Papanek Foundation, University of Applied Arts Vienna, believes his design philosophy is more timely than ever. “Papanek’s approach became shorthand for a socially responsible attitude to design, as well as a challenge to western assumptions regarding the role of design in every-day lives,” she says. “It had enormous influence in terms of foregrounding design as a political activity that can include or exclude specific groups.”

There’s little doubt that Papanek’s early life helped shape his career. He arrived in New York in 1939 at the age of 15, having fled Nazi persecution in Europe. He enrolled at the Cooper Union where he studied architectural design, hoping for a career as an industrial designer. He experimented, creating interiors and furnishings, and even set up his own studio in 1946, which never really got off the ground. Papanek took up his studies again, this time at Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s school in the Arizona desert.

The more he learned and made and the more he interacted with his fellow students, the more critical he became of industrial design. Rather than abandoning the field, however, he opted to use it to convey new ideas and explore different ways of connecting with people. He sought to educate, collaborate and investigate, eager to utilise the reach and power of design without succumbing to its consumer-driven instincts.

Meeting American architect R. Buckminster Fuller, and working alongside contemporaries such as designer George Nelson, media theorist and philosopher Marshall McLuhan and graphic designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, all helped to shape Papanek’s views on design’s ability to do more than simply create products to feed the appetite of consumer culture. Like him, they were pushing the boundaries in their chosen fields, developing avant-garde concepts and working to their own agenda.

“Throughout the 1960s,” says Professor Clarke, “Papanek gave lectures, read the works of alternative economist E.F. Schumacher (who advocated small-scale localised economies), and headed the design programme at North Carolina State University, where he put into action some of his ideas for health and design.”

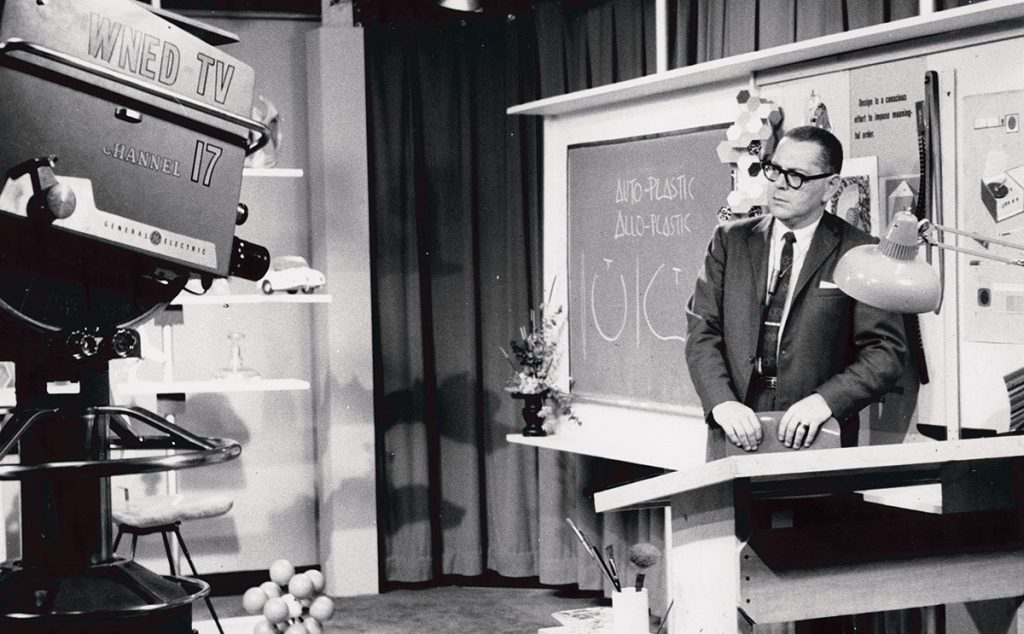

Aware that reaching people was key to disseminating his ideas, he began working on a TV show about design that aired throughout the USA. At the same time, he was writing and travelling, working with groups around the world to try to bring to fruition his ideas for an improved life experience. Navajo, Balinese and Inuit communities were just a few of the peoples he observed, investigating the work they did in the specific environments in which they lived, and the products they needed to fulfil their work. His approach was always in response to what was happening in his surrounding environment.

“His regard for other cultures was very much part of a contemporary movement to look beyond western culture for alternative models of design,” explains Professor Clarke. “It might be termed ‘cultural appropriation’ now, but he defended this by saying that he always co-designed with indigenous groups and was not the great design genius but rather a team worker.”

Within the design community itself, opinion over Papanek was split, with many of his contemporaries scathing about his negativity. He was relentlessly disparaging about his own profession – designers, he said, were a “dangerous breed”. He berated art schools for teaching students to create with corporate consumerism in mind rather than their fellow humans, and was highly critical of the decision to use materials and techniques that contribute to air pollution and landfill.

From our perspective in 2018, with the seas awash with plastic and our throwaway culture out of control, Papanek seems like a visionary. “His experience spanned the 20th-century history of design,” points out Professor Clarke, “so his work covers the whole spectrum. He was totally informed by the transitions in design’s meaning, and societal and historical role.

“His emphasis on anthropology and co-design, which now lies at the core of studio and corporate practices alike, forced the transition of design from making beautiful forms to a process of critical and political engagement.”

Victor Papanek: The Politics of Design, until 10 March 2019, Vitra Design Museum, Switzerland; Victor Papanek: Designer for the Real World by Professor Alison Clarke, (MIT Press), out 2019

DETAILS

Photography courtesy of University of Applied Arts Vienna, Victor J. Papanek Foundation and Vitra Design Museum

Words Catherine Coyle