Kirsty Lorenz’s floral paintings do much more than simply record the beauty of nature

Kirsty Lorenz had been in Fife for just a week when she unearthed a new art studio. “I’d been putting notices up in shop windows,” explains the artist, “when I was told to go and talk to Marjorie Ward, the station master.” When Marjorie produced a huge bunch of keys and unlocked the semi-derelict buildings on Platform 2 at Ladybank Station, Lorenz could see she had stumbled upon somewhere very special in which to develop her practice.

“I was among the first to take part in the Adopt a Station scheme, and I don’t think I really knew what I was taking on,” admits the artist. The scheme offers small businesses, organisations and local people the chance to occupy abandoned station buildings for nominal rents.

“For £1 a year, I had the station restaurant, which dates from around 1850,” she smiles. The building’s listed status meant she had to engage the local authority planning department; with funding grants from the Railway Heritage Trust, Business Gateway and Fife Contemporary Arts, she was able to transform the space into a series of studio rooms where she can paint and display her work. The platform itself also provides a viewing gallery of sorts; each time a train arrives (Ladybank is a fully operational station), a new audience gets a glimpse of her vibrant floral canvases hanging in the windows.

Ten years on, Lorenz now owns the studio rooms and has once again participated in the annual Fife Opens Studios event, this time welcoming more than 500 visitors through her doors. With her work rooted in nature, moving to Fife and away from the city made sense. Flowers have always been the focus of her work; initially, she took a very cultivated approach, focusing mostly on single stems. But, in 2013, a grant that allowed her to visit the Outer Hebrides to study the wild flowers of the machair (the unique grasslands of the western coasts) changed the direction of her work.

“Faced with all these amazing flowers in North Uist, I felt like a kid in a sweet shop,” she recalls. “In the sheer joy of observing them, I started making posies. They’d fade so quickly that I would leave them behind, on walls, and it felt in some ways as though I was leaving them to the fairies. That was how the ‘Votive Offerings’ project began. I could see the potential to develop this idea and explore the notion of these posies as prayers, gifts or offerings, but it also involved a message about the environment, too.”

Once her concept became clearer, in 2013, Lorenz began painting a series of 50 images, exhibiting them at the National Galleries of Scotland two years later. They were pinned, unframed, to the wall in an installation that not only showed the precision of her work but intention behind it.

Having previously worked on bigger canvases, the artist now tends to work to scale, showing these wild flowers as realistic but injecting an element of representation to the work. “There’s a lot of fiction in there,” she says, motioning to Votive Offering No.90 – White Rose after Mary Delany, that hangs in her studio. After studying the work of the 18th-century English painter, who produced over a thousand botanical studies, Lorenz has incorporated elements of Mary Delany’s practice in her own work.

Neither could be considered strictly as a botanical painter, but both paint with a mix of accuracy and poetic representation that elevates their work beyond photorealism, allowing them to explore deeper themes. “Each posy in the ‘Picked’ series has a film that goes with it, showing me choosing the flowers,” says Lorenz. “This taps into the sense of absence and that idea of taking something away.” She is very conscious of what she selects and she never picks anything she knows to be rare. “The wild flowers are abundant and are part of a life cycle. I hope that what I’m making gives new life.”

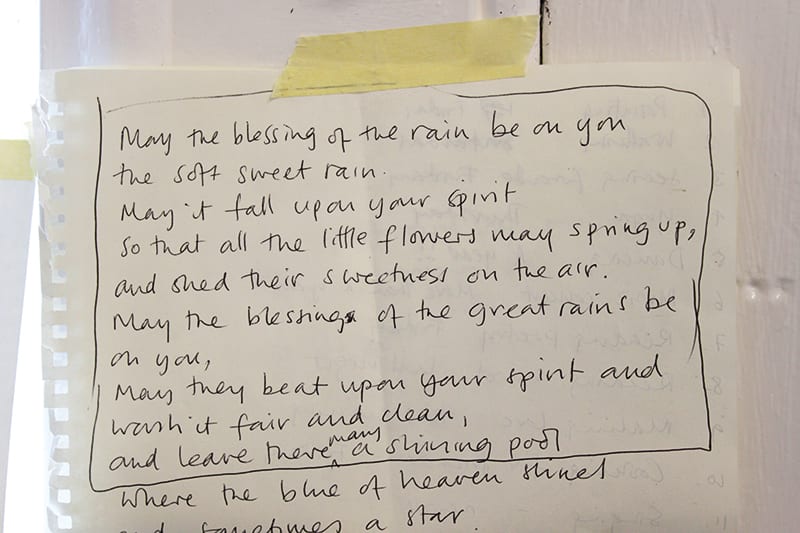

Recognising the ritualistic nature of her practice, the artist often uses excerpts from Celtic prayers and verse, integrating words into some of her paintings. “There’s an element of helplessness in the face of the environmental impact we see. I paint in the absence of being able to do anything else, so in a sense it’s like a prayer, a wish.

“I’m not religious but, like many people, I feel a profound universal connectedness when I’m engaged with nature. This feeling is joyful but also has great pathos, particularly in relation to the transience of life and beauty and the fragility of the environment. It’s hard to know if my work will evolve to new subjects, because for now I can’t see beyond ‘Votive Offerings’. I feel I’ve only just begun.”

Words Catherine Coyle